Collegare risorse epigrafiche e fotografiche con HTML+RDFa

Un esempio basato su CIL VI 1375

Linking epigraphic and photographic online resources with HTML+RDFa. An exploration based on CIL VI 1375

Presentation for the Workshop Encoding Metrical Inscriptions Workshop 14-15 Novembre Università di Foggia. Iniziativa organizzata nell’ambito del PRIN PNRR 2022 “Epigraphic Poetry in Ancient Campania” (cod. P2022SFXHC – CUP D53D23019820001). In collaborazione con Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici, Lettere, Beni Culturali, Scienze della Formazione - via Arpi 176, Foggia

Research supported within the cooperation of Università di Foggia with Bibliotheca Hertziana Max Planck Institute for Art History, Rome.

While Photographic Collections as the Fotothek of the Bibliotheca Hertziana have many Photographs of inscriptions, or of drawings of inscriptions, Epigraphic Databases contain editions of inscriptions with images. This different perspective is a decisive one. There is of course richness within the encounter of the different perspectives.

Metrical inscriptions may be intuitively associated with a more deep connection between text and context, but as these are not my field of research I will develop my argument on an example which is not immediately relevant to the topic, and I am certain metrical inscriptions experts will not fail to draw their own parallel cases.

I claim in this text that there is no technological obstacle to a comprehensive linking of information recorded and available online, which can be simply enriched with qualified links in the most common and widespread formats to deliver immediate important results with tools in the hands of everyone.

Getting quality content in quality formats, with relevant semantics online, is a much more urgent and challenging task than implementing large infrastructures or newer technologies.

Searching for research

I will try to show with a practical experiment how we can build knowledge by linking using the expressiveness of the languages of the web, which surpasses that of simple argument, if associated and accompanied by this textual argument. Linkage from the web-based-and-digital world to the printed-material world are bidirectionally faulty and hard to make without specific expertise ane FAIR-washing practices have made the complexity of this interrelation even more of an hindrance for researchers who need to navigate it.

The researcher (scholarly or not) is, in facts, the underestimated missing link, not any software or tools. Numerous collaborative tools, analogue and digital, exist and are actively used, so, no such tool, and no specific digital tool can actually claim to close any part of this gap.

We still need a lot of work to be in a position to fight the mass censorship

, to use Eco's words, to which the web contributes so vastly, now at the speed of a artificial intelligence, building false and unreliable contents vertiginously fast, while real knowledge still and always will need painstakingly long time and effort.

My practical exercise will consist of a naïve step by step experiential path among available documents online, to show how their availability alone, without connections is activated and made valuable only by proper connections.

While this experience will resonate in that of any one who has done some research, I propose here a further experiment, as I encode within this same text this connectsion as RDFa, assigning where needed the necessary entities and structures to make the path followed semantically relevant and machine interpretable, thus connecting at a fine granularity the addressed resources.

Collecting data

I will start from a record in the Photographic Collection of the Bibliotheca Hertziana, follow its link into a website of the Musei Capitolini and then move to the Epigraphic Database Rome.

I will follow links from there to explore how much information can be actually connected to get the best possible knowledge of a single object.

It should become evident how there is more real and direct value for the exploration of the network of information in a argumentative knowledge graph connecting in one specific and non unique way these resources than there can be from the extraction of value from quantitatively collected data.

The fragmentary nature of the data and the actual available data, scanty by nature, clashes in the end in front of the bibliographic barrier, that is, the innaccessibility of quality full texts of publications quoted as structured and unstructured data.

This presentation is in itself an example of one such path, that I would like to call an argumentative knowledge graph (AKG). This paper with a simple tool like RDFa Play can be directly visualized as data and it can be imported as is into a triplestore. Here I parse the HTML with vis.js for some additional example representation of the embedded data. Not to claim their usefulness, as often happens, but to claim their uselessness de facto, compared to the actual argument which makes its way across this network without any further visualization need.

Photographic Collection

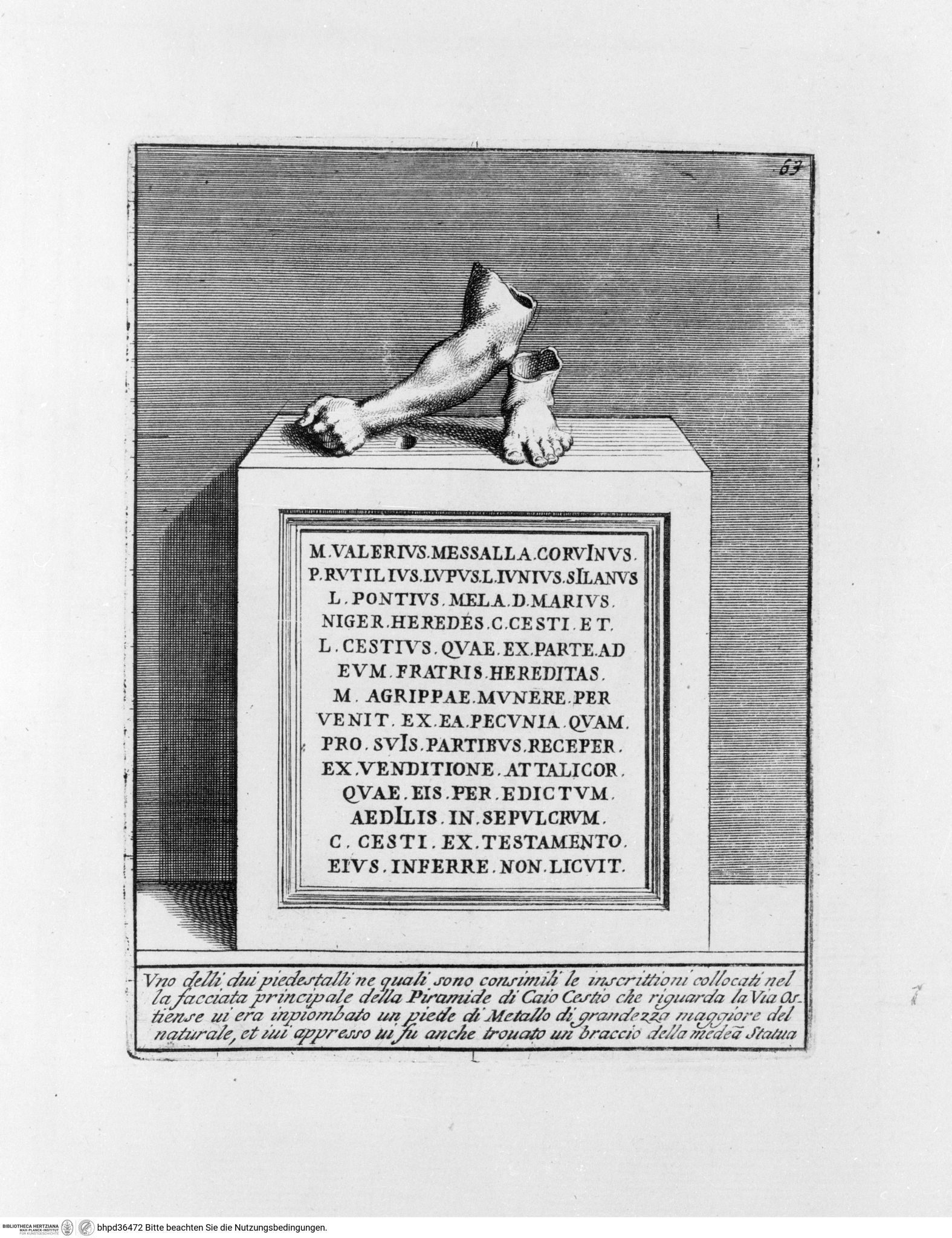

My starting point is an object catalogued in the Fotothek, with a bibliographical reference to CIL VI 1375: Statuensockel mit Inschrift des Caius Cestius

, curated by Regina Deckers and Christoph Glorius at least since 2017 with updates until 2023.

Landing on this page we learn about a statue base with an inscription now at the Musei Capitolini, found

vor der Pyramide

, which is the Pyramid of Caius Cestius.

The inscription dates before 12 BCE

and non-autoptic measures are provided for the inscription field.

A link is given to a page hosted by the Musei Capitolini.

The

photo (bhpd71012z) of the front side with the inscription was

a donation

by Malter Barbara who took the photo about 1982/1983.

Embedded Linked Open Data

There are a few more links, visible to the machines only as such, for indexing related to the object and photograph:

these three values associated to three different controlled vocabulary, and aligned among them, make for a good deal of alignment of the object.The aligned vocabularies are based on the shared MIDAS Thesaurus, maintained by Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte - Bildarchiv Foto Marburg and used by the consortium of photographic collections called Arbeitsgemeinschaft kunsthistorischer Bildarchive und Fototheken (AKBF).

The injection into structured data for the website of the Catalogue of the Fotothek from this Thesaurus is implemented following the guidelines of the NFDI Culture Knowledge Graph and has been done by the author of this paper with a SKOS based implementation. Anyone, crawlers by search engines and bots feeding Large Language Models included, could follow those links, especially when they will be part of rich results of common searches in the web. We are however not going to follow those links for now. We are also not going to look at web resources available online which replicate the same or part of the same information like Bildindex and Europeana for the Fotothek, but we will look at some aspects of Pharos later.

Following links to the Musei Capitolini

I was already redirected away from the focus of research, in my quest for content. As I am looking for actual information in this experiment of navigation history, I already found some. Additionally, thanks to the full dataset direct availability, I learn that

Es handelt sich um einen

der beiden mit Bronzestatuen bestückten Sockel, die einst vor der

Cestius-Pyramide standen. Reste der Bronzestatuem sind durch Druckgraphik

belegt. Heute trägt der Sockel die Gewandstatue der Julia Domna (Inv- Nr. S

49).

There is no explicit connection with other images which actually depict the same object, for example the etching on the right here, from "Gli antichi sepolcri, overo Mausolei romani et etruschi, trovati in Roma & in altri luoghi celebri : nelli quali si contengono molte erudite memorie" (1704), which is however an interesting early representation, by Pietro Santi Bartoli. So, I am not going to follow that lead, I will instead look for the other of the two named in the record.

Following links to the Musei Capitolini - continued

There is no link to any web-available record about this statue, which probably is simply not among the objects photographed in the collection.

We do not know which one of the two inscriptions we have and how do they differ.

We are told that these two statue bases were in front of the Pyramid.

Bibliography points to

These two publications, however, are not linked as resources neither to a bibliographic catalogue record (yet).The Druckgraphic mentioned in the paragraph attesting the information provided may be exemplified by photo bhpd36472, which we have seen just now.

We all agree that there is no point in pointing fingers to missing information in web resources because their completeness is relative to scope and aim of the collected information, and we all know how much work it takes to collect and enter such information at a good quality standard. So, this page is very rich in connections and primarily useful information to make one's way through other additional resources available, although less links than expected can be followed without a further search.

Foto bhpd71012 and negative d/7290

The Statuensockel mit Inschrift recorded as OBJ 08054714 in the Fotothek contains an Ausschnitt

from a photo of the object preserved at the Musei

Capitolini with identifier SCU 02386, also a photo by Barbara Malter. The photo (bhpd71012) is probably related to negative d/7290 of the Capitolini, listed on that page.

The page of the Musei Capitolini is unfortunately not maintained any more apparently and its accessibility is not very reliable, despite the precious information contained and published there. It is only thanks to my collegue Klaus E. Werner that I could consistently access this resource.

Hence, accessibility and availability of the linked resources cannot be guaranteed for this resource and its content at the moment.

Musei Capitolini

On the page for SCU 02386 one can learn of a record, by Maria Rosaria Stefanangeli, which gives a bit more information about the inventory number and we can see 4 different negatives, documenting clearly the text and the three visible sides of the statue base, which I reproduced here. Actually, if one still has in mind Julia Domna, named on the Fotothek's page, it is possible to modify the semantically meaningful URN and retrieve information about that as well. SCU 00049, which actually also provides a view of the statue base from the top. Foto Col 07642

The image of the inscription at the front is actually marked as "Malter" and may be the same as bhpd71012 in the Fotothek. Five negatives are named and for four of them a URN can be constructed.

The XVII century inscriptions

The last two images associated to the statue base in the website of the Musei Capitolini show also that there are additional texts on the same statue base, on each side. Both are dated 1681 within the text itself (MDCLXXXI). The size of the photos does not allow to read much.

On the side to the left of the ancient text we read from d/19907

]NCISCUS FANUS COS

]AN SODERINUS COS

]BERTUS URSINUS COS

]CUS ANT DEGRASSIS PRI[?]

M DC LXXXI

On the side to the right of the ancient text we read from d/19906

FRANCISCUS FANUS[

FRAN SODERINUS [

RUBERTUS URSINU[

MARCUS ANT DEGRAS[

M DC LXXXI [

Conservatori e Priori

It seems plausible that these two inscriptions are copies of the same text, inscribed in the same circumstance and for the same purpose in one creative act, so without being one the copy of the other.

Claudio De Dominicis, MEMBRI DEL SENATO DELLA ROMA PONTIFICIA Senatori, Conservatori, Caporioni e loro Priori e Lista d’oro delle famiglie dirigenti (secc. X-XIX), Roma 2009 lists these names at page 56 and 119 of the PDF, which does not correspond to the pagination of the printed book, as notified in the PDF itself.

1681-1/7 - Francesco Fani della Regola, Co.

Francesco [F. Antonio] Soderini di S. Eustachio,Roberto Orsini [Ursinus] di

Pigna - (Cred. I, to. 35, c. 119v).

1681-1/7 - Marc’Antonio de Grassis [Grassi]

de Monti priore, Co. Giovanni Francesco Vespignani di Trevi, Prospero della Molara di Colonna, Alessandro Bentivogli di Campo Marzo, Alessandro Fusti di Ponte, Giovanni Matteo Grifoni di Parione, Francesco Ferrini della Regola, Leonardo Severoli di S. Eustachio, Orazio Cardoni di Pigna, Pietro Zonca di Campitelli, Giulio Sinibaldi di S. Angelo, Giovanni Battista Vitale di Ripa, Nicolò Callimachi di Trastevere, Francesco Brandani di Borgo - (Cred. I, to. 35, c. 119v).

Editions of the XVII century inscriptions

In this list, findable with a Google Search, Cred. I, to. 35, c. 119v

stands for Credenzone I, tomo 35, Catena 119v

, which is the collocation in the Archivio Capitolino.

COS

stands for Conservatori. PRI for Priore dei Capo Rioni, often corresponding, like in this case, to the

"caporione del Rione I" (Monti).

These four magistrates were top figures of the Rome administration system between 1223 and 1870. They always signed together all completed projects. Which activity was signed off on these monuments is however not known to me and I have to give up investigating this further. However, the PDF referenced above gives us some more important details, placing the dating of these inscriptions between July and October of 1681.

The following is a screenshot of the edition of these texts, kindly pointed out to me by Silvia Orlandi. Without this suggestion the present exercise would have had a very quick end.

Forcella is based on a quantity of manuscripts as the introduction details, which we are not going to investigate but probably include the ones referred to also from De Domenicis.

More from the Musei Capitolini Website

The Entry in the Musei Capitolini page, would have even more to say.

There are four links in the description, apparently to other entities in the Musei Capitolini, two of which land on parts of a "Cippo" of M. Valerius Messalla Corvinus: SCU 01018 , and SCU 01032 .

The first seems to be unrelated given the findspot.

The images of the latter instead are interesting, because they also carry inscriptions of the Magistratura, which seem to be even later than the ones on NCE 02386.

The PDF list takes us to the last quarter of 1698,

1698-1/10 - March. Giovanni Battista del Drago Biscia, Filippo Fonseca, Giuseppe Sorbolonghi [no Sorbelloni] - (Cred. I, to. 35, c. 194).But this base cannot be the other statue base, or base of the column which held a bronze statue, as the Musei Capitolini Catalogue tell us, because it does not have the inscription. The actual base with inscription is there and can be found at SCU 01883 and the printed Catalogue claims it also carries on the sides inscriptions from 1681. But there are no photos of the sides.

SCU 01883 and its later inscriptions

Google Books has a copy of V. Forcella's book, already plundered above for a screenshot. One can find there the two inscriptions, each in two copies, one with and one without stemmas, as can be seen below.

This text, reported to be on the sides of the statue base which carries the text of C. Cestius testament, acquiring the land for the Pyramid, is revelatory in same way because the italics of this edition, as we have learned from the previous image from this book is the missing text. So, what Forcella reports on the side of the stone with the C. Cestius text as missing, and of which we have no image from the Musei Capitolini, matches exactly what we have on the images of the piece of the statue base without text for which the images on the website of the Musei Capitolini are actually available. This also explains why the record on the Musei Capitolini Website speaks of a 'part' of the cippo, perhaps.

The Second Statue Base has been cut in two parts

We have found online until now three identifiable objects.

- SCU 02386, the statue base on which we can see the first text (later we will see that this can be identified as EDR093684), and Forcella 178 on the two sides, with the statue of Giulia Domna on top, for which we have photos of all sides, except the one facing the wall from the Musei Capitolini.

- SCU 01032, the back half of the statue base with text (later we will see that this can be identified as EDR103369), and Forcella 198 on the sides, for which we have photos of all sides from the Musei Capitolini.

- SCU 01883, the front half of the statue base with text (later we will see that this can be identified as EDR103369), and Forcella 198 on the sides, for which we only have a photo of the front side in EDR but none of the sides and nothing by the Musei Capitolini.

If this consideration was right, because we have dated the texts on the sides from the lists of the Conversatori, we could say that the dating provided in the Museum catalogue for this text does not correspond, which would be however of minor gain. Also, it remains a mystery why the image of the text is related to the atrio of the musei, but we do not have photos of those, while there is documentation of what seems to be the back of that.

In the Musei Capitolini

Up to this point the web offered hints and reference information for an increasing number of aspects of information about the object from which I started this experiment. The Museum catalogue has wonderful pictures of the statues, but there are only thumbnails of the inscriptions and only of those which are considered more important. Also looking at the Museum with Google Arts & Culture does not help,

even with the aid of the catalogue to find orientation. We are short of two halves of the texts from the sides of the half basis with the textus altero

.

I failed the experiment. After checking anyway the catalogue from the Musei Capitolini available at the Bibliotheca Hertziana, instead of remaining online only, I went to the Musei Capitolini on Friday, 23 June 2023 to find out. From the web resources one does not even know really where are the Statue Bases now. They are easy to find, however, in the Atrio/Galleria of the Palazzo Nuovo, reached from the underground passage. The following are my own images taken with my smartphone during that visit.

Livia and Julia Domna

In the Musei Capitolini - Forcella n. 198

Being in Rome, it did not cost much to check, and here we have the missing images to confirm that the text edited by Forcella is this and that the supposition that S 1032 is the back half of this stone may be correct.

Matched images for Forcella n. 198

I have tried to match the images with the commonest tools, and the result is ugly but provides the argument with a depiction of the complete texts.

There is no database of inscriptions from Rome of this period as far as I know, otherwise I could have contributed there if they did not know yet.

In the Musei Capitolini - the back halfs of the inscribed blocks

There is a statue also on top of the back half of the statue base on which we have seen Livia. We knew about this from the Musei Capitolini Website, we just did not have the statue.

In the Musei Capitolini - the back halfs of the inscribed blocks

But because I had found

the missing two halves of the texts of 1698,

and I still had time, and I had paid the ticket, I went on searching, and I found also the back of the Statue

base on which there is Julia Domna, it was not far.

In the Musei Capitolini - Forcella n.178

With this two images, also for the two versions of Forcella n. 178 we have almost all the text.

Google Arts & Culture @ Musei Capitolini

Looking at the Museum with Google Arts & Culture does help to learn that there was, as one could expect, a statue also here until recently. The angle of the photos does not allow to see the texts, but it is indeed an additional piece of information which one can collect.

In the Musei Capitolini - Fasti Consulares

We also find the lists referenced by the XVII century inscriptions, because the Fasti Consulares are there in the Museum.

So, going to the Museum was very useful. All pieces of the bases could be found. Of course without knowing from the web-based searches what to look for, those would have remained supports for nice statues and nothing else.

Of course the quality of my pictures is turistic and it does not even stand close to any sort of documentation photography.

Now, we can go back to the record we started from, because there is another piece of information from the Fotothek's object "Statuensockel mit Inschrift des Caius Cestius", which can be explored, that is, the CIL reference.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) Online

With a bit of patience, and avoiding seemingly low-hanging fruits, in iDAI, one can find the page with the edition of the text from the first edition of this volume of the CIL of 1876. The entry in CIL, is quite informative, and we are looking at images with side OCR in multiple viewers, which is a plus.

CIL VI 01375 documents both the inscriptions on statue bases found near the Cestius Pyramid. The two statue basis are nearly identical or carry at least an almost identical text. CIL VI 01375a main text on statue base 1 and the other copy, CIL VI 01375b on another statue basis 2. CIL VI 01375a would be the text indicated as primary by CIL and CIL VI 01375b the "altero exemplo" which, starting at line 9 has a different layout. This layout distinction allows to easily say that CIL VI 01375a is the text on SCU 02386 while CIL VI 01375b is the text on statue basis composed of SCU 01883 and SCU 01032 if we accept the point above, or simply on an initial base 2.

The CIL text, composed and edited as Forcella edited its own corpus also tells us, with references, about the first movements of the two statue bases. One would have to find those references, which would be interesting also to try to date the time at which the two bases were cut, in the XVIII or XIX century, in any case, after the inscriptions on the sides were produced and had performed their function at least for some time.

On the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum Website I did not find related materials at the time of checking it in the early summer of 2023.

The inscriptions on the Pyramid

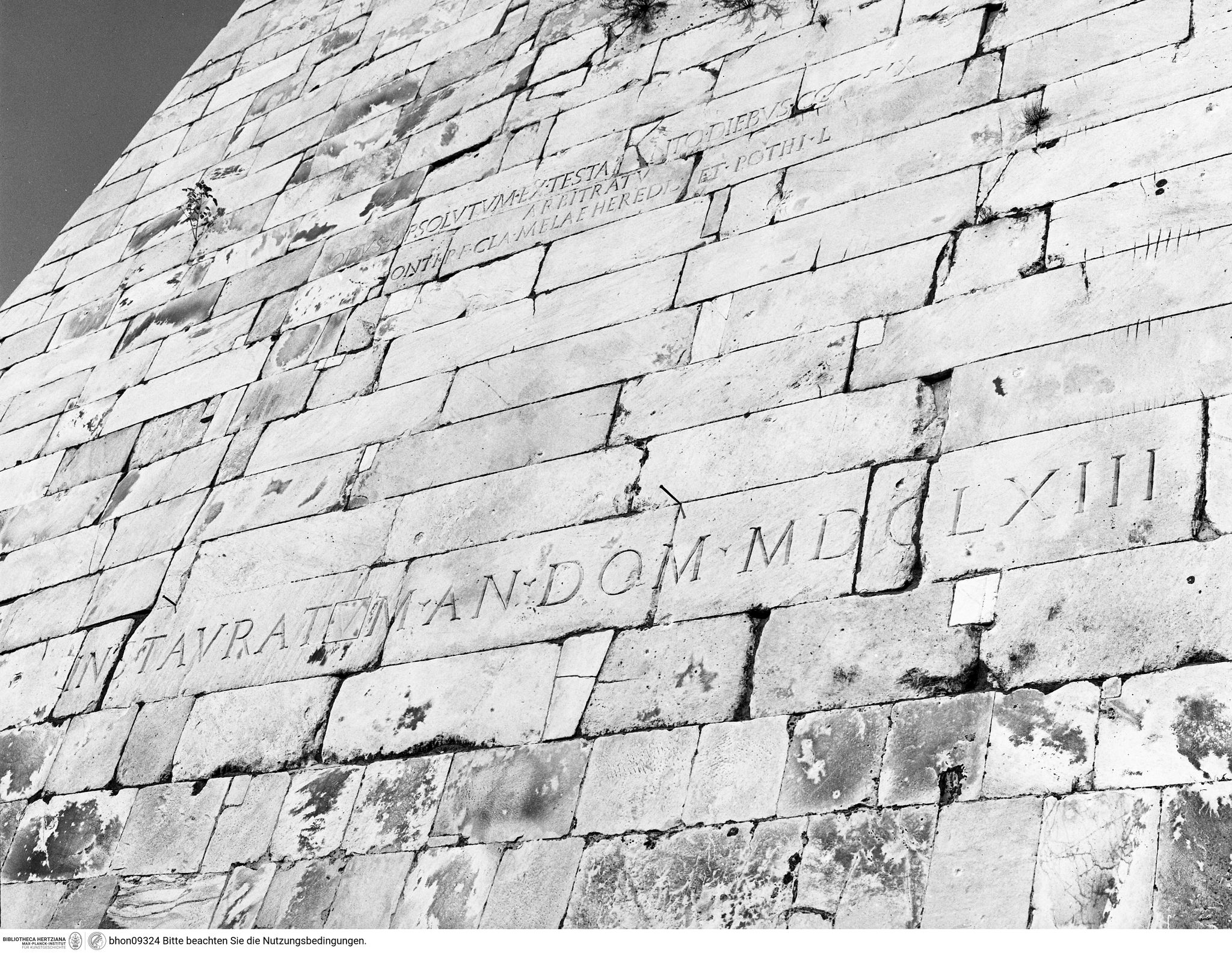

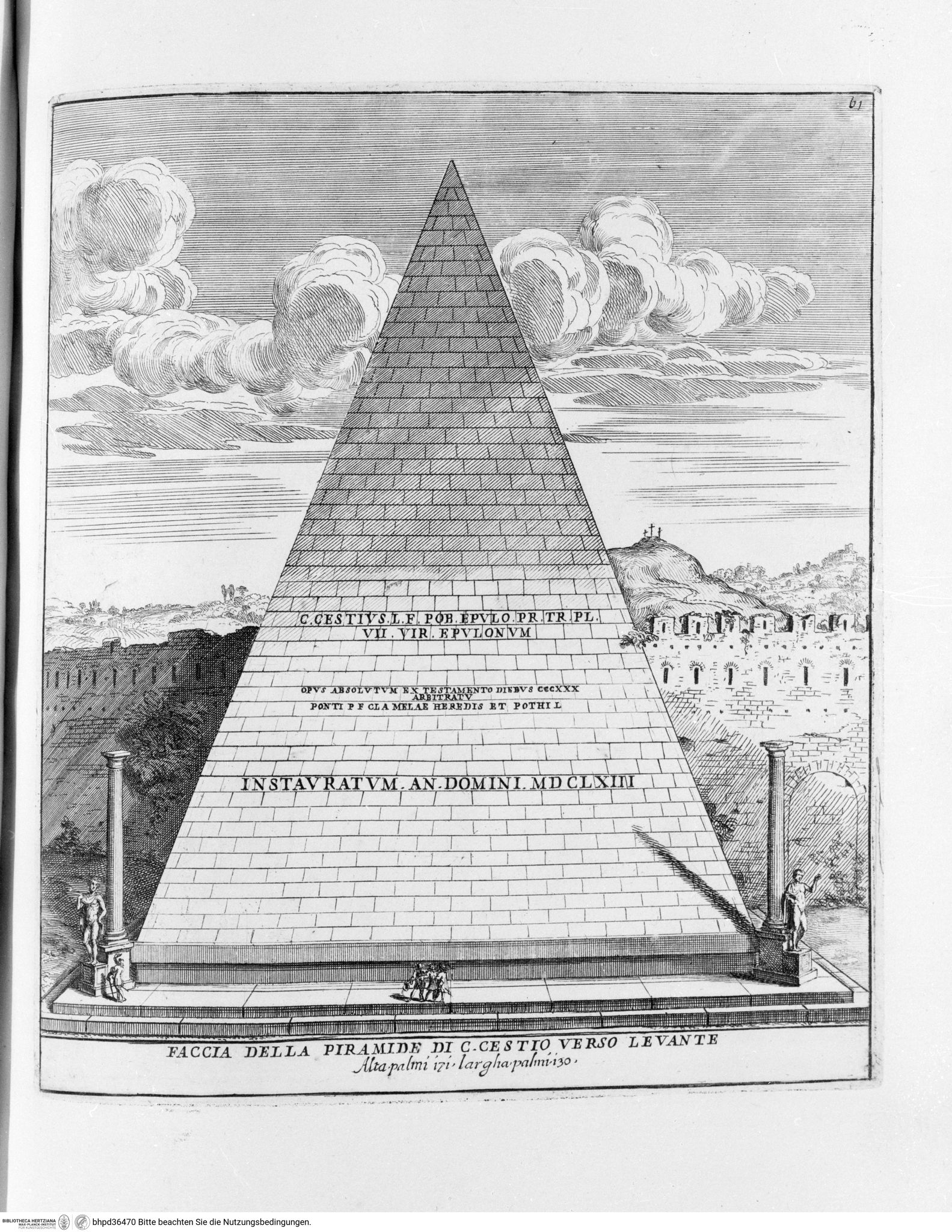

The statue bases were found as Pope Alexander VII restored the pyramid and excavated the area. With the help of Daniele Pellacani I could read the text of CIL which specifies that the excavation was done to dig out the base of the Pyramid (stylobate ). This happened in 1663, as attested by the inscription on the Pyramid itself, depicted also in a Photograph by Cesare d'Onofrio in the Fotothek.

Images related to the restoration of the Pyramid

In facts the Fotothek has several other depictions of the Pyramid of Caius Cestius, before and after this renovation which digged to the base of the pyramid.

This first image is a cyanotype of the Pyramid, in a drawing earlier than the restoration, in the famous album by Heemskerck, Maarten van, Heemskerck-Album II, dated in the Fotothek 1532/1536, more than a century ahead of the restoration.

Tav. 47: C. Cestio septemuri epulorum sepulcrum pyramidali forma hodie quoque integrum in Via Ostiensi,

propre portam nunc Sancti Pauli cernitur, Tav. 47: Vedute der Pyramide des Cestius

Viewer

Tav. 47: C. Cestio septemuri epulorum sepulcrum pyramidali forma hodie quoque integrum in Via Ostiensi,

propre portam nunc Sancti Pauli cernitur, Tav. 47: Vedute der Pyramide des Cestius

Viewer

The second one, always easily accessible from the Online Catalogue of the Fotothek, is by Cavalieri, Giovanni Battista de and is dated there to 1569

Images related to the restoration of the Pyramid - Restoration

Many other images of the Pyramid are available and can be easily found in the catalogue of the Fotothek, or simply using a search engine. The following example depicts exactly the restoration which unearthed the statue bases with the inscriptions.

This drawing is dated 1665 from the book IL NUOVO TEATRO / DELLE FABRICHE, ET EDIFICII, / IN PROSPETTIVA DI ROMA MODERNA, / SOTTO IL FELICE PONTIFICATO / DI N.S. PAPA ALESSANDRO VII

NUOVO TEATRO DELLE FABRICHE, ET EDIFICII... 1665

The collection of etchings is available online as such, for example in the Bibliotheca Hertziana Digital Library, but also as a digital edition which comes with a digital map of the places depicted by the etchings in the book.

The restoration of the Pyramid - Context

To give some context, while the Pyramid, dated by these inscriptions to between 18 and 12 BCE, and once thought to be the tomb of Romolus or Remus, the city wall was there since Aurelian built it in 272 CE. The system of towers was added only recently by the predecessor of Alexander VII, Urban VIII Barberini (See: Piero Maria Lugli Urbanistica di Roma 1998, p. 46 e 108-110).

Searching for Pyramids and Alexander VII one quickly meets the story of the Duke of Cérqui who issued a request to build a pyramid in reparation for an accident with the Course Guards. The Internet archive has extensive reading about this in The history of the popes, from the close of the middle ages : drawn from the secret Archives of the Vatican and other original sources; from the German by Pastor, Ludwig, freiherr von, 1854-1928, p.110-111

It is also uncomplicated to find an image of this other Pyramid and its inscription.

If we were to follow on all hints generously provided by the web we would also indulge in tangential searches for a Medal struck by Luigi XIV, and could go on down that path very long, but this matter seems almost entirely unrelated to the actual focus of the current enquiry. Because in the web it easy to follow on links which lead far out of scope and focus.

What this excursus tells us is also how easily confusing can the web become, and how terribly and badly needed are precise and controlled metadata and information like those maintained by scholarly databases.

From the Photographic collection non-digital collection back in the web

We have left a dead-end, let us go back to searching in the Photographic Collection to match contents which are not yet in the catalogue. This is a bit like going to be museum and makes the experiment a failure, but it is worth to see what else can be found that can lead to further online resources.

It is a matter of minutes, without technical skills or expertise, to easily make one's way to the section "Roma Urbanistica", to find a Box with the name "Porta San Paolo". Within this box there are relevant images and printed references which send the user to the Box about Piramide Cestia which is in the section "Roma Antichità", few steps away. Here one can find a print of a page from the Cod. Chig. P. VII 13, Fol. 56 from the Bibliotheca Vaticana, bh055081, with a note "Rom Cestiuspyramide und Entwässerungskanal zum Tiber"

Chig.P.VII.13 in the Vatican Library

The manuscript, part of the Fondo Chigi is luckily fully digitized by DigiVatLib and is available via IIIF. All drawings seem to be related to works related to the water management of the river Tiber. The description and the OPAC entry skip unfortunately folia 42r to 90r, where the drawing photographed in bh055081 occurs, but this section is however very interesting for the pyramid and its inscriptions, as it places the pieces in context. f. 4v contains a more complete index of the contents of the manuscript, listing also the folia which interest us. What follows is a sort of reading by myself.

Pianta del sito, livelli della Piramide di Cestio alla porta di S. Paolo 56

Disegno stampato della medesima 57

--- Disegno della connessione?? della medesima 58

Pianta della stanza della medesima 59

--- della medesima .... 60

--- col disegno d'una colonna della medesima e del capitello et ??? 61 - 6r

Disegno delle colonne, e loro basi, che sono nelli angoli d'??? 63r

Chig.P.VII.13 in the Digital Vatican Library

We learn from these drawings, for example, that while bhon09324 is a photo of the side of the pyramid outside the walls (verso levante), most if not all drawings and etchings, at least in the current contribution, are of the other side (verso ponente) within the walls. The Fotothek has complete coverage of all sides, and some drawings simply get the placement of the inscriptions wrong (see above). f. 57r shows the position of the columns and statue bases on the angles of the pyramid and gives hints, although not 100% clear, on the position of the inscriptions, both recorded and drawn, one together with the two sides of the pyramid and the other with the detail of the capital.

I am not sure about the meaning of these drawings and about what the reconstruction on folio 61r means. It sounds a bit stretched to say that the details on f. 62r may correspond to the ones on f. 57r, so that the inscriptions were on the outer side of the pyramid and the columns on the inner side, given this additional drawing with the base, inscription and column. This drawing and the one on bhpd36472, agree with regard to which of the two copies of the text carried a piece of bronze statue, that is SCU 02386.

Web to Streetview

We could get a similar effect to that of the manuscript overview, with Google maps.

Other Images related to the restoration of the Pyramid

The inscriptions on the sides of each stone are later than the book with the etchings of Falda and may have to do with the completion of other restorations in 1681. Perhaps related to the management of waters in the Tiber as attested by the Manuscript. If the restoration of the Pyramid and the necessary excavation were actually motivated by this kind of concern, I do not know.

From Photographic Collection to Online Epigraphic Databases

The web is a sea with many islands and you can jump, by design, from one island to another, seemingly entirely unconnected, as in no other sea. Even better if the page is indexed by search engines and a search with parts of the information available leads directly to the page we do not yet know about. Scholarly resources still do far too little of the far too simple search engine optimization practice to allow for this to happen.

So let me jump to another resource, with a completely different perspective on the same objects of research.

I happen to be quite sure that this inscription must be part of the Epigraphic Database Roma (EDR). Because this is a different field of research, Ancient History and namely Ancient Epigraphy, it is of no surprise that the Fotothek does not point to this resource and viceversa.

Epigraphic Database Roma

Searching in EDR by Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum reference we land at EDR093684 Here we find, apparently for the same object some quite differently sorted information in comparison with the Fotothek.

Measures are given with more precision and we get some extra classifications, for the type of inscription and inscribing technique used, which are however not directly linked to formal vocabularies. We will see later that there is more to find out about this. Here some details

Mensurae:We learn quickly a great deal of important information, in a concise and straightforward way.

Alt.: 82

Lat.: 78.05

Crass./Diam.: 46

litt. alt.: 2,4-3

Status tituli: tit. integer

Scriptura: scalpro

Lingua: latina

Religio: Pagana

Titulorum distributio: oper. publ. priv.que

Virorum distributio: ord. sen.

Epigraphic Database Roma Links

The bibliography is here vaster and we find links to two other web resources:

- EDH https://edh.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/edh/inschrift/HD031696

- The Ohio State University Center for Epigraphical and Palaeographical Studies https://kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/100272

The most important bit of information we find is

Textus gemellus invenitur ad EDR103369and, in facts, there it is. This, as the sister record, carry a inventory number which can be compared to that of the Fotothek and the Musei Capitolini. NCE 2386 is associated with EDR093684 only. EDR103369 is associated to NCE 2385, of which we have already said, which makes the information nice and tidy.

Epigraphic Database Roma Images

Different images are listed with each of the two inscriptions, and are catalogued separately, although with a model entirely different from that of the Photographic Collection.

- 103369

- 103369-1

- 103369-2 This image is also linked to another website as source of this image http://ancientrome.ru/art/artworken/img.htm?id=3895 whose attribution and responsibility are opaque, but whose Russian origin is flagged out.

- F014055 fetched from EDH (see below)

- F014056 fetched from EDH (see below)

The automated imports fetch both images because of the link to EDH, which, following on CIL, has only one entry for both "copies" of the text. F014055 is an image of the text on SCU 01883. F014055 is an image of the text on SCU 02386.

Arthur E. Gordon and Joyce S. Gordon Collection

EDR093684 (and not EDR103369) provides a link to https://kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/100272. This entity, decorated with a stable identifier (http://hdl.handle.net/1811/100272), publishes 5 different photos without any other metadata about them, as depictions of an epigraphic entry. We get to know that the photos are part of the Arthur E. Gordon and Joyce S. Gordon Collection

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Unfortunately, neither the metadata or the images or the bibliography from this resource seem to increase our knowledge of the inscriptions.

Epigraphic Database Heidelberg

HD031696 from Epigraphic Database Heidelberg is referenced by both EDR records. Beside the text the record contains several images, separately catalogued, described in a IIIF Manifest.

- F014055 depicting EDR103369 which we already know

- F014056 depicting EDR093684 which we already know

- F031416 which is a set of notes by Géza Alföldy on a printed copy of CIL 06 01375

- F032339 depicting EDR093684

- F032340 depicting one of the two versions, unclearly

- F035780 depicting EDR103369 and documenting probably a copy presenting at Museo della via Ostiense in 2013.

Georeferencing of the

find spot is usefully provided by EDH in a separate and related database, and can be found only here. G019487

identifies Via

Ostiensis, Grabmal des Caius Cestius

and is related to other entities like Trismegistos place 2058 and Pleaides place 423025 which however are larger Place

entities labelled with "Rome".

Links back to EDR (

EDR103369) are also provided as well as to

Trismegistos, which in turn provides links

and aided searches from the bibliography, but yet no direct link to the

available bibliographic resources.

This links open up to additional related resources by greater place and bibliography, which I am not going to further explore in this context.

Aggregators and Harmonization - Europeana

EDR093684in the EAGLE portal.

Via the EAGLE Aggregator EDR and EDH are also harvested by Europeana, and we can find the item from project 2058806 (EAGLE Europeana) relatively easily. On this page, in addition to what we have already seen in the source for the aggregator, we find that the EAGLE Vocabularies have been used for alignment of the descriptive information in EDR. Let me stress that only the aggregator has this alignment information, in a similar way to the MIDAS Vocabulary used by the application, and also here this alignment is not used for any practical purpose.

The same inscription is classified differently, but aligned to the same EAGLE vocabulary for type of inscription, in the aggregated record for HD031696, as we learn from the Europeana Aggregator.

Europeana

We should have started from here perhaps. Europeana aggregates data from the Fotothek at the Bibliotheca Hertziana as well as data from EDR and EDH. We would have found all in one place, already aligned to one model. So I tried.

- I searched for

CIL 06, 01375

as the most obvious way to get to the inscriptions and the Fotothek record. No results. - I tried to match the field name in the advanced search. No results.

- I tried searching the items one by one: EDR103369 hits one record for the entry, and one for each of two images with less and less updated information, hence not worth mentioning here; EDR09368 hits one for the record and one for image, as above.

- Same image as for EDR103369 is found looking for HD031696, with information as above, but not aligned.

- No results for any identifier from the Fotothek about the base we started from.

- What we do find is clearly related, yet technically entirely unrelated and scattered in what should be an aggregator meant to facilitate exactly this kind of cross search.

- All links are internal links to replicas of information within europeana with the only exception of the link back to the provider of the information.

- We do find several interesting items for further exploration searching for

Caius Cestius

, which include some of the items mentioned here, for the example, the photo of the drawing in the Album of Maarten van Heemskerck. - Images cannot be linked, as the IIIF Manifests are not exposed from the user interface.

Perhaps it was not my lucky day.

Vocabularies and the Artresearch platform (Pharos).

Departing from the somehow dissatisfactory experience above, we have to acknowledge however that the Europeana connections takes us to a level of connection by links which we have not properly looked at until now: Vocabularies. We have listed the EAGLE Vocabularies Terms used for alignment by the epigraphic databases and visible via their aggregator. We have listed the Midas Vocabulary alignment in the structured data of the Fotothek for one object.

A further enterprise which replicates the contents of the Fotothek must be named, for its large effort in harmonization and alignment of vocabularies, which is the Pharos Artresearch platform, although still in beta release.

Here we need to search for Caius Cestius

to get to our item, but

we get there.

The replica of the information from the Fotothek activates directly the aligned terms, we can click on each and get to the related items from other providers to the Pharos platform. While that functionality is deferred to filters in the Fotothek Katalog, and is realised only as links in the EAGLE aggregator and in Europeana, here the result of the alignment is materialised directly and we also get to see with icons which providers use the same terms, hence we get an idea of how much shared they are. Entities aligned are also more then those we have seen until now.

Matching ends, aligning vocabularies

While Pharos Vocabularies actually link up the resources they align, the EAGLE Vocabularies leave this to their users. Let us see how much connection we can get and especially if we do learn something new from these connections, except for opening up to more examples of entities tagged in the same way, which is of course already useful for some purposes.

While the entities for Photographer, Current Location and Institution are a very useful local navigation hint, the other terms, which are present in other resources offer ways to connect and align.

Pharos Sockel

is aligned to Getty AAT 300264092, an Object Facet but has no declared direct correspondence.

The AAT value for Sockel provided by the MIDAS vocabulary is 300080499 as we have seen and the EAGLE Vocabulary for Basis aligns to a DAI Vocabulary term, which cannot be retrieved.

But we know that EDR and Europeana as well as the Fotothek and Pharos refer to the same conceptual thing.

We know we are speaking of the same thing,

and the SKOS version of the MIDAS vocabulary adds the missing alignment to GND.

Skulptur

is not used in the Epigraphic databases but both Pharos

and the MIDAS Vocabulary refer to the GND entity.

For Pharos however this is identical to AAT 300047090, while

MIDAS claims is only related.

Marmor

is aligned in EDR with a concept from an unreachable resource of the DAI, https://archwort.dainst.org/thesaurus/de/vocab/?tema=2383.

In Pharos it is considered identical to AAT 300011443.

and so it is by the MIDAS Vocabulary.

We can safely say the same for the EDR and EDH.

The discordant typology of inscription is relevant only in the epigraphic database.

Unfortunately, if we were hoping to see the ends join up via the vocabularies, we have not found what we were looking for, or at least not quite.

Vocabularies offer however many further ways to navigate related information, whose relevance is limited for the purpose of this paper.

The Queen of Links

I did not enter the business of addressing all the bibliography provided in the related entities explored until now in the Fotothek and in Epigraphic Databases, in relation to the case study in object.

I did not do the research part dealing with the scientific publications, which would have most likely made obvious most of the bits of information found out above, because the aim of the experiment was to test the effectiveness of the online resources and their informativeness, coherence, connection and usefulness to facilitate the progress of human knowledge.

We could encode all bibliography and match entries by shared bibliography, or keywords associated to the titles cited of course, not to mention the people authoring and contributing to those resources.

In most cases it is also the case that in the explored resources there is no link to follow for any of the bibliographic entries, even where there could be one, at least to a catalogue entry, if not a permanent link to a openly available publication (or any of the many configurations in between these two extremes).

Bibliography, the queen of all types of scientific linkings, remains thus not actionable in the online resources explored. I have listed above the two references of the Fotothek's Object page, here is a further bibliography list from the other resources I have found.

Bibliography

- CIL 06, 01375, cfr. pp. 3141, 3805, 4688-4689. Linked and discussed above, with additional notes from Géza Alföldy at EDH

- ILS 0917a Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae is available at the Internet Archive, which allows also to link the exact opening https://archive.org/details/inscriptioneslat01dessuoft/page/202/mode/2up

- A.E. Gordon and J.S. Gordon. Album of Dated Latin Inscriptions (Berkeley and Los Angeles 1958-1965) no.16-17

- E. Nash. Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Rome (New York and Washington 1968) vol. II, 321-323, fig. 1089

- I. Calabi Limentani. Epigrafia Latina. 4th ed. (Bologna 1991) 207-209, no. 32bis

- Boll. Arch., 13-15, 1992, pp. 8-10 (R.T. Ridley)

- Walser, Römische Inschrift-Kunst (2. Aufl.: 1993), S. 50f. can be searched in Google Books.

- AE 1994, 0103, available on JSTOR for those who have access, refers to the above literature.

- SupplIt Imagines - Roma 01, 0155

- F. Feraudi-Gruénais, Ubi diutius nobis habitandum est. Die Innendekoration der kaiserzeitlichen Gräber Roms (Wiesbaden 2001) 137, Anm. 832.

- F. Feraudi Gruénais, Inschriften und Selbstdartellung in stadtrömischen Grabbauten (Libitina, 2), Roma 2003, p. 110 nr. 157

- A. Kolb-J. Fugmann, Tod in Rom. Grabinschriften als Spiegel roemischen Lebens, Mainz am Rhein 2008, pp. 57-58

- Musei Capitolini. Le sculture del Palazzo Nuovo, 1, Milano 2010, p. 223, nr. 32

- Musei Capitolini. Le sculture del Palazzo Nuovo, 1, Milano 2010, p. 220, nr. 25

The only observation I can make towards the aims of this experiment is that similarly to vocabularies the potential augments with the age and relevance of the cited resource. CIL has the most connections to it and remains the primary source of information.

This comes also as no surprise, no one can expect an "exhaustive" bibliography for its own research questions on a helpfully available online record for a document of interest, it is simply not reasonable.

RDFa encoding

So, the surface information the web has to offer is for the investigation of a specific document when considered as a single possible navigation history of one single non-expert user is as varied as we could expect, available in diverse ways, and limitedly accessible, incomplete in many respects, connected only to some extent.

Yet, it is indeed of the best quality possible to the state of the art, is useful, rich, detailed and multifaceted.

We cannot complain about it, we can confirm that the work to be carried out is still endless, and that the emergence of tools which spread uncontrolled information is going to be a major hindrance in the pursuit of knowledge.

There is however an eminently huge gap in the information available which is hard to explain when looked at theoretically, but is easy to understand if one has ever entered information in a database or published resources online. The lack of qualified links and across resources.

I think that the missing links, beside those of the alignment of vocabularies bibliographies and other so-called "controlled", but I would say, to date,s hardly "controllable" areas of information.

These missing links are those related to the several layers of connections among the different individual statements that one can make collecting and organizing individual resources.

I have thus made a second experiment. I have added to this text RDFa statements manually to link all statements and entities with each other explicitly with a standard vocabulary. This text becomes thus in a second way also a dataset.

RDF choices

RDFa can be encoded in many ways, here I have encoded only the following formats, to facilitate my own experiment. For example:

@resource @typeof to declare a resource and assign it to a class. For example, resource="#bhpd71012" typeof="sch:ImageObject" is an RDF statement which says that the entity "bhpd71012" is a ImageObject, aka, a photo. @resource @property @about to declare relations between two entities. For example, resource="#bhpd71012" property="sch:isPartOf" about="#fotothek" is an RDF statement that says that the entity called "bhpd71012" is part of the entity "@fotothek", which represent the Fotothek. @property alone connects the same parent entity to a textual value within the XHTML element. @resource @property @href declares a relation with a resource defined outside of the current text. property="dc:relation"

href="https://trismegistos.org/place/2058" declares a relation with the Trismegistos entity named in the @href attribute.A small "+" with dotted border is added with CSS to show where these statements have been added as attributes of any of the element of the text, or added alone in empty span elements. There are about 600 in this text.

This is not meant as a competitive alternative to any other way to encode information, is simply the most obvious tool available to connect existing heterogenous resources. It would benefit from stable URIs, which are however another topic of enquiry.

Semantic Layers

With RDF one can say anything, it is an extremely generic format. Here I have only identified Digital Objects and their relations to Research Organizations using schema.org vocabulary (the model used for Search Engine Optimization by Google). I have tried to be systematic about the relations among the entities and I have provided relations to the main available vocabularies.

Beside more known conceptual reference models like CIDOC-CRM and widely used ontologies like BIBO for the bibliographic information, named vocabularies and sources, I have used properties and classes from the ontology of La Syntax du Codex, which I developed some years ago and tested in another research environment. This is a structural guide to the description of manuscripts. Its applicability to any written artefact has been clear since its publication, and here I have applied it in a very simple way to the two statue bases and their inscriptions.

Another less known model, the so-called

epigraphic ontology

, for the description of inscription is the result of a large collaboration,

which I helped write up some years ago, and is tailored to the need of inscriptions. This helps especially in

the distinction of units related to text and support, with a core descriptive distinction

based on the recognition of the binary nature of an inscribed object as text on a support

and as support with a text

. So, I have used that as well.

Additionally, I have added connections among the described resources, and alignment of the vocabulary.

Networks and Graphs

A so-called Spaghetti Graph with all nodes in this presentation is not very useful, or readable. It may convey a sense of unity and coherence, but does not tell us more than what the data has already said, especially in this case, where the triples reproduce the content of the simple flow of the text.

Network Analysis on such a dataset would also be of little relevance due to the network variety in qualification of the relations and classification of nodes, as well as its limited size.

Let me present instead two graphs, one with only the relations which can be extracted from the data available

online, and one with only the triples which are added here, excluding also all those triples which are functional to the presentation (title, author) and not related to its contents.

I have accomplished this, by adding a custom data attribute to the triples, @data-type

- equal to

akg

for what has been added here, - equal to

source

for what was available elsewhere and is only replicated here, and - equal to

functional

for all what could not fit the previous two categories.

The source data of the following representations is hence the very same text you are seeing, and a javascript library (vis.js) is used to parse it and represent it as a graph. Color represent different types of entities.

[data-type='akg'][data-type='source'] grouped by sourceCleaning the Network

In the previous graphs we can observe something which we knew already: the content of a contribution is coherent (hopefully), and the resources out there are only some times kept together by sporadic links.

If we also clean up relations which are not directly relevant semantically to a researcher, e.g. URLs, we have very little, but a quite clear picture of what resources we actually have.

[data-type='source'] grouped by source and limited to research-relevant information (no urls)Network and argument as ways to establish a possible order among the pieces of information

[data-type='source'] grouped by source and limited to research-relevant information, excluding classificationWhat we take home from this reduction process is that all what really matters are qualified links between existing entities with their information baggage. Explicit and direct ones.

For example, the single link added by virtue of sending an email was more important than any long process to integrate resources in platforms and aggregators.

We can see that Epigraphic databases are more and better connected among them, yet there is only that one link joining the lonely Fotothek to them. And another lonely link to join the Fotothek to the resources of the Capitolini, making of the Fotothek, unexpectedly, the actual bridge among all these resources, hence enforcing the user-centred experience. If someone else than me had done the same experiment, the result would have been different.

Information Quality

This paper lists more than 40 available images online related to one another in several ways and adds to those other 30, while it imports even more from other resources but the documentation of the object in question remains perceptibly and factually incomplete.

I have assigned relations of the type "depicts" (crm:P62_depicts) to the sources, assuming their implicitness.

We know we have double images of the most ancient texts and partial images of the texts on the sides. We do not get to know from the online resource even which is which or what text is on what stone and what their relationship is. We need an argument to make sense of that information and many more statements, which I have tried to add and document here.

But of course this example alone is not a paradigm of the general situation, which is definitely much more complex as the items become more complex, multilayered and interconnected.

The actually important information, the one adding up knowledge of the objects, discovered by following up links provided and initial information found online, came up primarily in my opinion from:

- Visit to the Museum (Musei Capitolini)

- Hidden Web resources (Musei Capitolini)

- Personal conversation (see Aknowledgements)

- Paragraphic information (notes in the Fotothek)

- Hand-written notes on paper (Fotothek)

- Connection of resources in physical collections (Fotothek)

Graphs by type of relation

I have run another small declarative experiment on the data I have encoded here to see if we can evaluate which kind of information has more to say.

I have tried, always with vis.js javascript, to split up the data in this paper in networks by vocabulary of the statements.

It seems plausible to say that, smaller, more focused models have a better chance at consistency, readability and at the end of the day results. From the same data one could show all depicted sides of the object at the different identifiable stages of their transformation.

Links, please.

Links to non-replicating resources, or to replicating resources which provide added navigation and content value, are very important for findability and for a richer network. Fortunately they have to be curated, hand-picked, selected and encoded manually to guarantee quality information, as well as any other piece of information. One needs to know where and which to pick and use.

We need links, to join up in the wider worldwide network. And not only internal links to make better sense of our own contents, but especially links to other resources, reaching out and letting the users reach out to other relevant resources. And yes, a generic link to a specific resource is more immediately useful than an alignment to a third one. Especially when crossing disciplines, the paths of a mapping can be longer, but indeed more fruitful than a generical and mechanical alignment, which can only be made relevant buy this network of connections.

A curated link, a wilfully structured semantic statement or group of statements, individually curated, is much more valuable than any number of machine-generated links and models.

The missing link could be a network of curated links which only question driven scientific research can produce. These need, on one side, ways to facilitate this linking, and on the other side reliable curated linkable resources.

Ideas for a todo list...

But what can we do to facilitate that? We cannot expect anyone to be crazy enough to write up papers in HTML+RDFa as I did here, only to realize that arguments in humanities research are also inherently datasets, just simply not usable as such without further curatorial layers. The following is my wish list.

- Print products from your digital assets.

- Publish openly.

- Prioritizing links outside of our own curated resources

- Digitize more, diverse material, openly and accessibly, avoiding as much as possible duplication (see point before)

- Encode bibliographies fully, making books and article reachable as quickly as possible

- Be linkable, exposing URLs to resources as explicitly as possible, preferring semantically readable addresses composed of information in the data.

- Identify areas of lacking information opening up interaction possibilities like crowd/expert sourcing.

- Surface structured data and alternative formats making them available.

- Automate layers of RDF statements extractions according to common standard vocabularies from texts, focusing on content, not on structure.

With IIIF and SEO implementations, as well as with the new Catalogue and the Vocabulary applications the Fotothek has stepped up towards these needs in full respect of its responsibilities.

We are not very good with links outside our own comfort zone, and we have no linked or operable bibliography, despite our institutional placement. We are working on those points.

... and a final consideration

As researchers we struggle to acknowledge the inherent similarity of our textual output to a page on the web, let alone to a dataset. Allowing those contents to be editable by others is almost a tabu, and collaborative editing is acceptable only when highly coordinated.

If collaborative editing of shared resources still is a pioneering enterprise (not a dream-like one, as many have been able to achieve it, like papyrology and numismatics), those of us who could not aim at this, may still work "the other way around" and insist on web-based collaborative products which strive to go further than their older printed counterparts.

Technicalities overwhelm the effort in many ways and hinder it largely.

Tools to write research products (articles, books, presentations, database entries) will always end up limiting the potential of the entire resources of the web, inevitably. We can however still embrace the freedom of expression offered by the web and renew a vow of responsibility for the quality of the contents we curate.

Aknowledgements

Many thanks to Silvia Evangelisti for letting me take part in this event. For their support in this experiment I wish to thank also

- Daniele Pellacani,

- Silvia Orlandi,

- Klaus E. Werner,

- Alessandro Adamou,

- Giovanni Freni,

- Johannes Röll, and

- Tatjana Bartsch.

Thanks for listening, reading, or even just scrolling down.